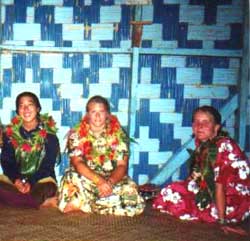

Hot on the trail: Jessica Stutte (center) and Meghan Claire (right) set out for the local hot springs with village kids near Delailasakau, Fiji.

Photo: Anna Lindhjem

While the idea of pairing experiential learning with academic discourse is hardly new, a new trend in applied and context-based learning does more than take students out of the classroom and into the field. It provides them with the means to explore new territories while turning their thoughts inward to personal goals and aspirations as well as outward to larger issues of social and environmental responsibility. In the case of the Institute for Global Studies, getting away from it all also means getting up close and personal, with field study and internships both domestically and abroad that give students the opportunity to do community service and environmental advocacy while immersing themselves in unfamiliar cultures and landscapes.

In his initial approach to this venture, David Adams, the brains and spirit behind the institute, cast back to his own experience as a student. “When I was an undergraduate and I was looking at the different study-abroad programs that were out there, it just seemed like everything was take, take, take; you’d suck up all the information about the culture and all the information about the environment, but you wouldn’t give back anything. I think it’s one of those things that went on unexamined for so long that we just took for granted that it was an acceptable way to go about things. You know, we’d have our cruises for adults and we’d have our study abroad for our students.” Adams determined to change all that. The Institute for Global Studies now offers its own unique brand of socially and environmentally conscious field study and internships not only in the U.S., in Alaska and Hawaii, but in Asia, the Pacific, and various other locations.

An anthropologist with an undergraduate degree in philosophy and master’s degrees in Asian religions and anthropology, Adams got his doctorate from the University of Hawaii, focusing on Buddhism and ecology. While in graduate school he also taught field study for the Wildland Studies program offered through San Francisco State University, overseeing a six-week course in Hawaii, which included a ten-day internship. “I hadn’t known until then that internships were such a hot thing among students,” says Adams, “and they could be offered in areas where students were able to really give back, volunteering in national parks, working on reef-ecology projects, and working with children in the inner city.”

An anthropologist with an undergraduate degree in philosophy and master’s degrees in Asian religions and anthropology, Adams got his doctorate from the University of Hawaii, focusing on Buddhism and ecology. While in graduate school he also taught field study for the Wildland Studies program offered through San Francisco State University, overseeing a six-week course in Hawaii, which included a ten-day internship. “I hadn’t known until then that internships were such a hot thing among students,” says Adams, “and they could be offered in areas where students were able to really give back, volunteering in national parks, working on reef-ecology projects, and working with children in the inner city.”

That course formed the impetus for the pioneer offering of the Institute for Global Studies, which was conceived by Adams in 1998. The Semester in the South Seas, based in the Hawaiian Islands, is a three-month, field-based immersion course in Hawaiian ecology and cultural geography. The program borrowed some of its inspiration and curriculum from the Wildland Studies course and combined the exploration of the area’s diverse ecosystems with an expanded month-long internship.

While the range of coverage was broadened from that of the course he taught through San Francisco State, the focus was tightened around the framework of Adams’s own personal vision. “Because of my training and my philosophical bent and ethos, I wanted to find internships where people were exposed to the environment or native cultures.” he explains. “That’s why I honed in on working with wildlife refuges, as well as native Hawaiian organizations and others that were promoting sustainable development, both culturally and environmentally … The growth in the philosophy and the mission statement of what eventually became the Institute for Global Studies revolved around field study and study abroad with a sense of giving back to society.”

Adams, whose own life appears to be a carefully crafted mix of introspection and outreach, explains his philosophy regarding learning and personal growth. “Philosophically, I don’t feel a standard university education as it’s currently designed is complete without a field component and an experiential component. It’s just not developing well-rounded students. To be honest, my feeling is that it’s just cranking out more urbanites.” Adams walks his talk, interspersing his time spent in the wilderness with travel and teaching. He admits that phones and the Internet have enabled him to maintain his contacts and orchestrate the institute’s activities from remote locations. He seeks not to refute technology or traditional education, but to augment and temper its effects with earthier as well as more spiritual and socially focused values.

Aside from its singular mission, the Institute for Global Studies is unique in several respects. Unlike many internship and study-abroad organizations, it accepts students who have not yet started college. “Taking a year off between high school and college is a popular trend these days, and we give those students a life experience so that they really come back a lot more mature than they left,” says Adams. In addition, the placement options for these experiences are distinct from those offered elsewhere. The Pacific was essentially uncharted territory for study-abroad options at the institute’s inception, and other areas that already boasted their fair share of field-based programs, such as Australia, lacked any with an environmental focus. And the program format itself is unparalleled elsewhere, offering students the opportunity to choose from among three internship options in any given location.

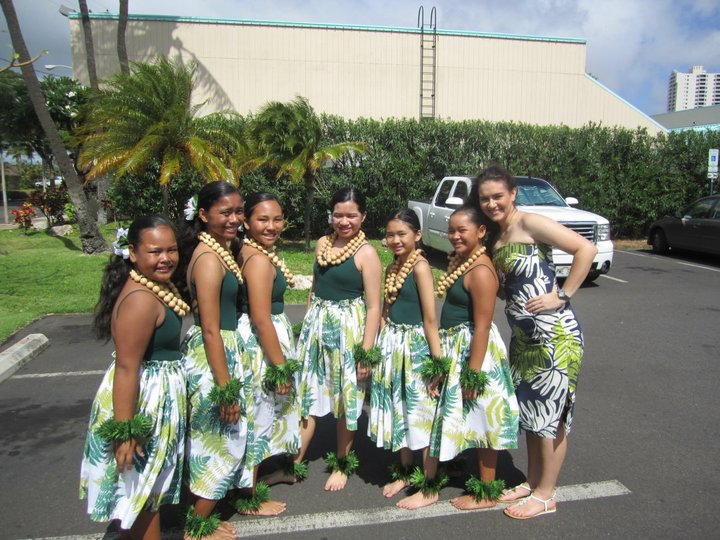

Local color: IGS students (from left) Tiffany Yap, Jessica Stutte, and Anna Lindhjem get decked out Fijian-style for a welcome dinner and dance.

Photo: Eric Nisbet

The institute’s internship opportunities are as varied in subject area and experience as they are in locale. Projects are available in everything from resource management, for which students might work in a rain forest and monitor and tag endangered birds, to arts and culture, with internships available in a community theater. Adams describes one project students engaged in last fall in which they worked with German researchers in Thailand’s Khao Yai National Park with a population of gibbons, a kind of ape found in southeast Asia. The students’ job was to track the gibbons down and get them acclimated to humans so the scientists could then do studies with them.

Other students, working in Honolulu, have taught in a children’s literacy program. Says Adams of this placement, “This can be a raw experience, working with low-income Vietnamese, Filipino, and Hawaiian children. With those kids throwing pidgin at them, our interns probably understand about half of the words coming their way, so they get a real cultural experience. Even in a month’s time most of my students walk away with a sense of accomplishment.”

Alison Metz, a former biology major and competitive swimmer at UC Santa Barbara, enrolled in the Semester in the South Seas program after hearing about it from two teammates who had participated in it. The course, which involves extensive backcountry hiking and wilderness camping amid the spectacular and diverse natural scenery of the Hawaiian Islands, draws its academic content from the lectures and readings of anthropologists, geologists, archaeologists, marine researchers, and ornithologists.

While Metz enjoyed learning about Hawaiian culture and religion and appreciated the workshops in volcanism and reef ecology, she claims to have benefited most from the time away from the daily grind to reflect on life and consider her future. “I spent a lot of time thinking about what I wanted to do, and that was of the greatest impact. I really learned to slow down, and I think that’s the best thing I could’ve gotten from the trip. I think I took a little bit of that home with me. When you’re in college, you try to fit eight thousand things in one day, and there, your task for the day might be setting up camp or collecting bananas or … free diving and picking algae off rocks to analyze … It was a slower way to live.”

Metz, who had never been camping before, also enjoyed that aspect of the experience. “I think I learned the most from the group interaction and the challenges of the hikes and the camping.” She tells of one particular experience that made an impression on her. “There was a hike that took five hours that went through eleven canyons and valleys that was a pretty big deal, because we wound up back in the forest where no one goes, and there was a local there who collected coconuts and bananas for us and made us dinner. It was an enlightening experience to realize people do live off the land that way.”

Metz, who had never been camping before, also enjoyed that aspect of the experience. “I think I learned the most from the group interaction and the challenges of the hikes and the camping.” She tells of one particular experience that made an impression on her. “There was a hike that took five hours that went through eleven canyons and valleys that was a pretty big deal, because we wound up back in the forest where no one goes, and there was a local there who collected coconuts and bananas for us and made us dinner. It was an enlightening experience to realize people do live off the land that way.”

Metz goes on to ruminate, “We’ve adapted in a very weird way, in that we sit at our computers all day, and it had a huge impact on me to live that way for six weeks and to realize that we’re actually supposed to be doing that … There you’re going to sleep with the sunset, you’re waking up with the sunrise, and everything’s different, even your body. I’ve never felt so healthy. And if you allow it to, it really makes you ponder what the point of life is — like, should I be outdoors enjoying the beauty of this world every day or should I be inside crunching on my laptop?”

Adams notes that the transition from urban living to the grittier conditions of the program is not always so seamless. “It can be challenging and painful on both ends at times. Some kids are very demanding and may not see why they have to sleep on the dirt floor, but they do.” He remarks that the end result is generally character expanding, however. “These kids are basically living out of a backpack, and there are a lot of trials to deal with living in remote villages or camping at all times … Once a person has done that on and off for three months, they’re a different person. I’ve had students come back and say that they’ve had to put their tents up in their backyards because they can’t stand being indoors anymore. So we’re actually reshaping their emotional reactions to the environment. There’s a physiological change that goes on if you’re outdoors for a duration like that. And it’s not about reading and it’s nothing you can study.”

The ability to take unexpected circumstances in stride is an essential quality for both the program’s staff and its participants, particularly where foreign governments and cultures are involved. In one instance that tested this flexibility, Adams and thirteen students were in Fiji during a coup, when there was an eruption in the military barracks and nine soldiers were killed. “The first thing I did was call [the States] to let all the parents know we were out of harm’s way,” says Adams. And while he and his employees are confident in their knowledge of the cultures and the political situations of the countries they visit, they exhibit great care in their handling of any unusual events that occur. “It’s part of our job to make a determination about the country and safety issues and then to convey them honestly,” he says. “If there is any kind of risk, we present it to the parents and then let them make decisions, too. They are major participants in all of this.”

Two of the most popular international programs offered by the institute, called Intern Around the World, offer a multicountry experience over the course of a summer or semester, rotating students to three separate locations. The first, in Hawaii, Thailand, and Nepal, features Buddhist studies, children’s advocacy, and environmental conservation. The second offers students a marine-science focus in Hawaii, Fiji, and Australia, with alternate choices for social service and ecological restoration projects.

Anna Lindhjem, who completed two years as a biology major at St. Michael’s College in Vermont and is now taking a break from traditional college education in Hawaii, enrolled in the Intern Around the World program as a concession to her parents’ desire that she stay engaged academically. “It was kind of a compromise between traveling and school,” says Lindhjem, who had been reconsidering the focus of her studies. “I got to earn credits and stay out of the classroom.” Not wanting to stray too far from her background in biology, yet interested in exploring something somewhat different, Lindhjem settled on the marine-biology focus for her multinational journey. “It wasn’t that hard to choose,” she says. “I’d never had any marine-science classes, and I figured if I liked it, I could stay and finish school in Hawaii and not have to go back to the mainland.”

Coincidentally, every student in Lindhjem’s session had opted for the same focus, and so they remained together throughout their three-country tour, rather than being split into groups. Each section of their journey commenced with a weeklong orientation and continued with the undertaking of various projects. In Hawaii, the students hiked and learned the natural history of the area, worked with a dolphin researcher and a sea turtle foundation, and did data collection and analysis projects. In Fiji, they underwent scuba certification at the Coral Coast and did marine research on a small island. The trip culminated in Australia, where the students traveled the mountains with an aboriginal guide, explored the Great Barrier Reef, and conducted research on Heron Island.

Of her experiences in the three countries, Lindhjem cites her stay in a village in Fiji as the most eye-opening. “The houses there are single-room shanties, but the people set us up with whatever they could. I had a mattress, and the family slept on the floor, and they had an outhouse and no electricity. But they treated us so well; we were offered everything they had.”

Lindhjem also tells of an experience working on the north shore of Oahu doing drift-net recovery with a sea turtle advocate. She explains, “It’s a common practice for fishing boats to cut their old nets loose when they’re old or ripped and leave them in the ocean. One net meets another and they’re just a tangled mess snowballing across the Pacific that wash up on our little islands … Turtles get stuck in them and they end up killing the reefs as well.” She estimates that she and her companions pulled up six thousand pounds of net in two days, and describes how their work encouraged the participation of island locals. “The second day we went out happened to be the Fourth of July, so a lot of families were out and setting up picnics, and they saw what we were doing and started helping. They wanted to know how they could do this, how they could continue to help. I think they saw what a difference a bunch of random people could make to clean up their beach, and it was really cool.”

Adams discusses the long-term effects of such experiences. “A lot of these kids are going to come out of this program and it’s going to be potentially life changing. What’s rewarding for me is that I may be dealing with the sons and daughters of lawyers and accountants and venture capitalists. That’s all they know, and they’re headed straight toward that course in life, but it just so happens that we cross paths and I get a chance to expand their horizons and kind of steer them toward alternative routes, whether that means fund-raising for nature conservancy or something related in some other way.” He tells of one former student, Andi Nelson, who performed a six-week field study in Hawaii, living in a Buddhist temple and writing a paper on Buddhism and ecology. On her return home, she added a minor in environmental studies and instituted a program of student-orientation wilderness trips for incoming students at her college.

In Lindhjem’s case, the program didn’t direct her to a single path for future academic pursuit, but opened doors to numerous possibilities instead. “I don’t know what I want to do with the rest of my life or with a degree,” she says. “A lot of things sound cool, and a lot of things sound fun.” She has decided that she isn’t interested in pursuing hard science, however. “I’m not so interested in how a cell works anymore. I’d like to know how all things work together, like reef ecology or even how humans came into effect, and how they affect their environment. I think I may be onto a bigger picture.”

Lindhjem credits her experience with the institute for her new interest in environmental science and ecology, and even for a turnaround in her feelings about school. “Being in a class with hardcore biologists, I used to pray for the animal I was dissecting … I think I’ve kind of known all along that it’s not what I’m into … It may be why I haven’t gone straight through school and gotten a biology degree.” Most importantly, she feels that a world of unlimited learning has been opened up to her through her guided travels. She sums up her experience, saying, “There was a sign we saw on the wall of a hostel in Maui that said ‘Be a traveler, not a tourist,’ and I think that’s what we really got to do.”